Introduction: Why Circular Design and Taxation Matters

In an age of climate crisis, resource scarcity, and growing environmental awareness, businesses, designers, and policymakers are turning towards models that regenerate rather than deplete. Among these, the concept of circular design and taxation stands out: a nexus where product lifecycle design meets fiscal policy. By aligning taxation systems with circular design principles, countries can move beyond linear “take-make-waste” models towards sustainable innovation, reduced environmental harm, and resilient economies.

Circular design refers to designing products and systems that maximize reuse, repair, remanufacturing, recycling, and minimal waste. Taxation, policy instruments, and financial incentives can either hinder or accelerate these efforts. If taxes penalize repair, or favour resource extraction over labour-intensive reuse, they unintentionally embed linear economic models into law. Conversely, well-crafted taxes and reliefs can reward circular design, decrease emissions, and support social justice.

This article explores how taxation interacts with circular design: what works, where the barriers lie, and how to craft policy tools that lead to sustainable innovation. Through examples, case studies, and policy frameworks, this essential guide aims to empower designers, businesses, and governments to harness circular design and taxation as powerful levers for change.

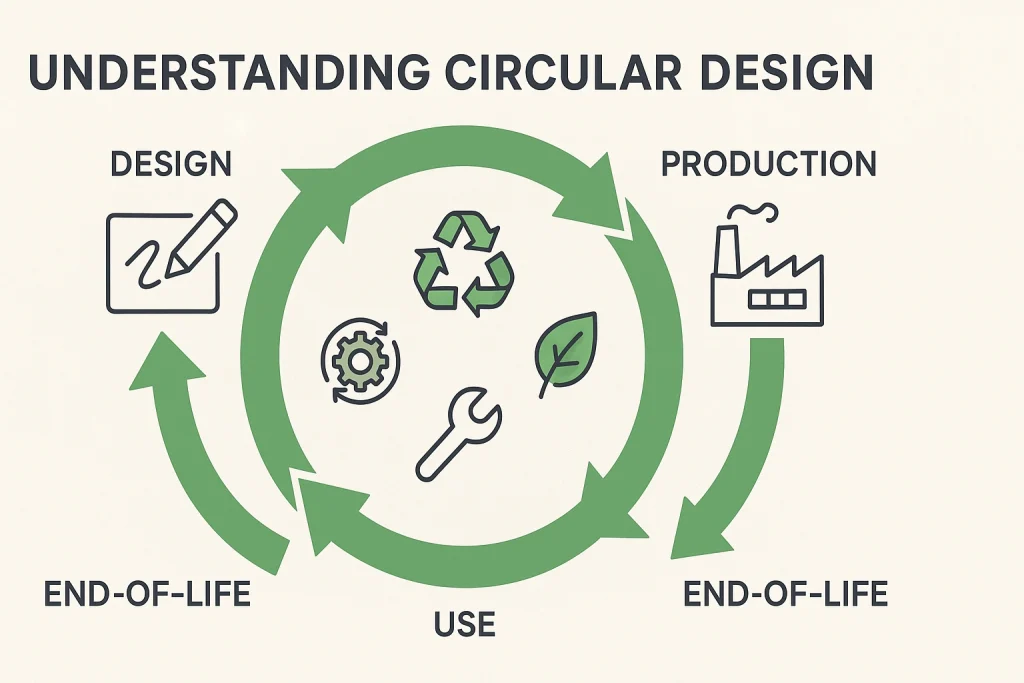

1. Understanding Circular Design: Principles & Lifecycle

1.1 Definition of Circular Design

Circular design is the practice of creating products, systems, or services with the explicit aim of minimizing waste and environmental impact throughout their lifecycle. It is guided by principles such as:

-

Design out waste and pollution — minimizing resource input, avoiding toxic or hard-to-recycle materials.

-

Keep products and materials in use — through repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing.

-

Regenerate natural systems — using renewable sources, enabling composting, returning materials to ecosystems.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a leading voice in this field, emphasizes that circular design embeds regenerative thinking from the very start: choice of materials, modularity, disassembly, repair-ability.

1.2 Product Lifecycle Stages: Design → Use → End-of-Life

To see how taxation intersects with design, we need to understand lifecycle stages:

| Stage | Design implications | Key circular design activities |

|---|---|---|

| Design / Production | Material selection, minimal waste in manufacture, design for disassembly and repair, modularity | Eco-materials, minimal packaging, avoiding mixtures, design for refurbishment |

| Use / Service | Encouraging longer product lifespan, maintenance, repair, leasing or product-as-a-service models | Repair services, warranties, leasing or sharing business models |

| End-of-Life (EoL) / Waste Management | Proper collection, recycling, ensuring materials re-enter supply chain, managing hazardous components | Waste collection systems, remanufacturing, recycling, take-back schemes |

At each stage, taxation or fiscal policy can either reward circular design or penalize it (intentionally or by oversight).

1.3 Circular Design Tools: Design for Disassembly, Reuse, Remanufacturing

Several tools, guidelines, and techniques help embed circular design:

-

Design for Disassembly: products designed so components can be taken apart easily, supporting repair, reuse and recycling.

-

Modularity: allows parts to be replaced or upgraded without replacing whole systems.

-

Material choice & traceability: using materials that are recyclable or biodegradable, avoiding composites that are hard to separate.

-

Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA): modeling environmental impacts across raw material sourcing, use, end-of-life.

-

Business model innovation: e.g. product-as-a-service, leasing, sharing, take-back programs.

These design techniques create the potentials that taxation systems can either nurture or obstruct.

2. What Is Circular Taxation? Concepts, Instruments & Policy Levers

2.1 Definition and Core Principles of Circular Taxation

Circular taxation refers to tax policies and fiscal instruments designed to encourage circular economy activities — that is, to reduce resource extraction and waste, extend product lifespans, and promote reuse, repair, remanufacturing, and sustainable design. Key principles for good circular taxation include:

-

Tax externalities: making sure environmental costs (pollution, waste, resource depletion) are internalized.

-

Incentivizing circular business models (rather than penalizing them).

-

Ensuring fairness and social equity (just transition), so that citizens and industries aren’t unduly burdened.

-

Transparency, legal clarity, administrative feasibility.

The European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform defines circular taxation as distinct from traditional environmental taxes by its alignment across lifecycle stages and its use of revenues to promote circular activities.

2.2 Economic Instruments: Resource Taxes, End-of-Life Taxes, Waste Taxes

These are types of direct/fiscal instruments used in circular taxation:

-

Resource / Raw Material Extraction Taxes: Taxing the extraction or use of non-renewable materials (minerals, fossil fuels etc.) to reflect environmental externalities. Encourages material substitution, less waste. MDPI research suggests these are essential to reduce bias in current tax systems favouring resource-intensive industries.

-

End-of-Life (EoL) / Waste Hierarchy Taxes: Taxes or levies at the disposal stage that penalize landfilling or incineration, promote recycling, recovery etc. For example, “waste hierarchy tax” proposals aim to push EoL treatments up the hierarchy (reduce, reuse, recycle).

-

Taxes on Pollution, Emissions, Carbon: Although more focused on emissions than design per se, also shape incentives in production and material usage.

2.3 Indirect Taxes: VAT, Customs, Tariffs

Not all taxes are direct; many policy barriers or supports come via indirect taxes:

-

VAT (Value Added Tax) rules / reductions: Repair, refurbishment, reuse services are often taxed at same or higher VAT rates than sales of new products, making reuse less economical. Some jurisdictions reduce VAT on repair services to encourage circular design.

-

Customs & Tariffs: Taxes on imports can penalize recycled or remanufactured goods (due to classification) or favour virgin materials with lower tariff barriers. Adjusting customs classifications can help.

2.4 Shifting the Tax Burden: From Resource Use to Labour

One recurring theme in research: current tax systems often impose high taxes on labour (wages, services) while taxing resource use or non-renewable materials much less. That creates a bias away from labour-intensive, circular activities (repair, reuse, remanufacture).

For example, from MDPI: “current tax system penalizes circular activities, which are generally labour-intensive… as opposed to new product manufacturing activities, which are generally intensive in materials and energy.

Shifting tax burden—reducing taxes on labour and increasing taxes on resource consumption—is proposed as one structural reform. This can make repair and reuse more competitive.

3. How Taxation Affects Circular Design and Circular Business Models

3.1 Case Studies: EU, Sweden, Others

Here are examples of how different jurisdictions have applied taxation + policy in ways that affect circular design:

| Country / Region | Policy or Tax Instrument | Effect on Circular Design / Business Models |

|---|---|---|

| Sweden | Tax relief on repair services; favourable tax treatment for reuse & repair. | Encouraged growth in repair and refurbishment businesses. Increased willingness for manufacturers to design for disassembly. |

| European Union (via EU Action Plans) | Policy frameworks proposing waste taxes, variable VAT rates, raw material tax proposals. EU Circular Economy Action Plan includes “getting the economics right”. | Push for harmonised tax treatment across EU members. Some nations piloting or implementing circular taxation elements. |

| Other | In some US / China / Germany / Canada programmes, tax incentives are offered for items produced from recyclables, or lower tax burdens for recycled material usage. |

3.2 Business Models Enabled by Good Tax Policy

When taxation aligns with circular design, several business models thrive:

-

Product-as-a-Service (PaaS): Instead of selling a product, owners retain ownership and lease usage. Encourages durable design, repair, refurbishment. However, PaaS can be complex tax-wise (VAT, ownership, asset depreciation, etc.).

-

Reuse, Repair, Remanufacturing businesses: Lower VAT on repairs, tax reliefs on spare parts, lower customs duties on recycled inputs make such business more viable.

-

Sharing / Access models: Peer-to-peer sharing, rentals. Easier if indirect taxes don’t penalize services over products.

3.3 Barriers & Unintended Consequences in Current Tax Systems

Not all tax systems are well-aligned. Several challenges:

-

High labour taxes make repair & reuse more expensive relative to replacing with new products.

-

VAT and classification issues: repair/ refurbishment services are taxed same as new sales; recycled inputs may be classified and taxed unfavourably.

-

Subsidies for polluting or resource-intensive sectors remain in many systems, offsetting any incentives.

-

Administrative complexity and enforcement: tracking recycled materials, monitoring compliance, defining tax bases.

-

Equity concerns: Resource or environmental taxes may disproportionately impact lower income households unless revenue is recycled or offset.

4. Designing Effective Tax Reform for Circular Design

4.1 Key Characteristics of Good Circular Tax Policy

Based on literature and practice, good circular design + taxation reform should:

-

Be life-cycle oriented: policies across design, use, EoL stages.

-

Provide clear incentives (not just penalties) for reuse, repair, remanufacture.

-

Shift burden from renewable / labour toward non-renewable / resource use.

-

Be stable and predictable to give businesses confidence to invest.

-

Use revenue smartly (e.g., recycling revenue into grants, rebates, training).

4.2 Equity, Just Transition & Social Impacts

Tax reforms must consider social justice:

-

Protect lower income households from price shocks (e.g., through tax credits, revenue rebates).

-

Support workers whose jobs are in high resource / extraction industries to re-skill.

-

Ensure rural or underserved regions get infrastructure for circular economy (repair shops, recycling etc.)

4.3 Administrative, Legal & Implementation Challenges

Some of the practical frictions:

-

Defining tax base properly: What counts as “recycled material”, “repair service” etc.

-

Avoiding double counting or loopholes.

-

Ensuring consistent classification (especially across regions / jurisdictions) to avoid unintended trade/ customs issues.

-

Setting rates that are high enough to change behaviour, but not so high to create incentive for evasion or unintended negative effects.

4.4 Monitoring, Compliance & Revenue Use

-

Monitoring environmental outcomes (waste reduction, emissions saved, lifecycle assessments) to assess whether tax levers are working.

-

Compliance systems: ensuring tax breaks aren’t abused.

-

Transparent use of revenue: e.g., using funds from resource taxes to fund circular economy infrastructure, R&D, design initiatives.

5. Global Trends and Future Directions in Circular Design + Taxation Policy

5.1 International Examples & Best Practices

-

The EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan (COM (2020) 98) includes significant emphasis on “getting the economics right”, encouraging Member States to use variable VAT, and experiment with resource tax, etc.

-

Swedish example of reducing VAT / tax reliefs for repair services.

-

Projects and studies (e.g., MDPI, European Environmental Bureau) that propose frameworks like raw material taxes + waste hierarchy taxes etc.

5.2 Technological, Regulatory & Social Drivers

-

Increased awareness of climate change, environmental damage, and resource scarcity.

-

Pressure from consumers for sustainable products, repairability.

-

Regulatory pressure (e.g., EU Ecodesign Regulations, Right to Repair laws) pushing for durability and repair.

-

Innovations in product tracking, modular design, digital mapping of material flows.

5.3 Forecast: How taxation will evolve in support of circular economy

-

More governments will likely introduce resource extraction / non-renewable resource taxes.

-

Likely increased VAT reductions / exemptions for repair / reuse services.

-

Greater harmonisation among jurisdictions (especially in trade blocs like EU) to avoid cross-border mismatches.

-

More integration of lifecycle assessments into tax law (e.g. product carbon footprint, materials disclosure).

-

Use of environmental tax revenues for green infrastructure, research, social support.

6. Recommendations for Businesses, Policymakers & Designers

6.1 For Designers: Integrating tax-aware design thinking

-

from first stages, consider how your product will be taxed: repairability, modularity, recyclable materials.

-

Use design tools that model end-of-life, resource usage, disassembly etc.

-

Document materials and parts for traceability, to help for classification, recycling.

6.2 For Businesses: Aligning strategy with tax policies

-

Monitor existing and proposed tax policies in your jurisdiction: incentives, reliefs, VAT changes.

-

Explore business models (product-as-a-service, leasing) that may benefit from favourable tax treatment.

-

Engage with policymakers / industry groups to shape fair tax reforms.

6.3 For Policymakers: Key policy reforms, case studies to emulate

-

Reduce VAT or offer tax reliefs for repair, reuse, remanufacturing services.

-

Tax non-renewable resource extraction and raw materials more heavily; remove subsidies for polluting industries.

-

Create end-of-life taxes that push disposal up the hierarchy.

-

Ensure clear classification in tax law so recycled inputs or reused parts aren’t penalized.

-

Build infrastructure and governance to support enforcement, monitoring, revenue recycling and equitable transition.

7. Conclusion: Toward an Aligned Future of Design and Taxation

Circular design and taxation are not separate topics—they are intertwined facets of sustainable, regenerative economies. When tax systems are aligned with design principles that promote reuse, repair, remanufacturing, and minimized waste, the outcome is more than environmental protection: it is innovation, resilient business, job creation, and a fairer society.

The path is challenging: overcoming legacy tax rules, classification issues, vested interests, administrative burdens. But globally, we are seeing promising policy experiments, frameworks, and business models that show what is possible. By anchoring design decisions within fiscal reality, and by shaping taxation to nudge behaviour rather than block it, we can move toward a future where circular design and taxation reinforce each other.

For designers, businesses, and policymakers alike, the opportunity is now: to build tax regimes that reward circular value, to invest in products built for longevity, to support reuse and repair, and to ensure that the cost of resource extraction and waste is not hidden but internalised. That alignment is essential for sustainable innovation—and circular design and taxation, together, are among the most powerful levers we have.

Credible Reference

For further reading, see Taxation for a Circular Economy: New Instruments, Reforms, and Architectural Changes in the Fiscal System (Sustainability, MDPI) for detailed proposals and global case studies.